Recollection:

A Small Casualty

of War

By S. K. Oberbeck

Recollection:

A Small Casualty

of War

By S. K. Oberbeck

I look at the faded, crackled snapshot--printed so pint-sized, I suspect, to save paper during the war. It's hard to make out the faces, but there stands a ragged line of little kids, playing soldiers, none over 10 years old.

I recognize my knobby knees, the skinny arms in a striped tee-shirt aiming a large stick like a gun, my tow-head nearly swallowed by my uncle's WWI doughboy helmet. I see my brother, unsmiling, his chubby arms crossed defiantly over his chest. I see the I-dare-you grins of Mertz, Lagerhausen, blue-collar kids who weren't even sensitive about being Nazis. I see poses struck in pure contradiction among my brothers in arms: tenderness trying like hell to look tough.

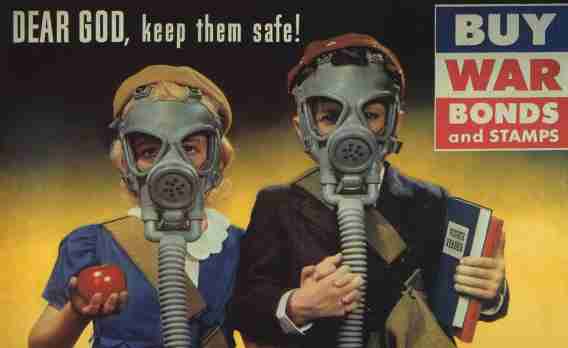

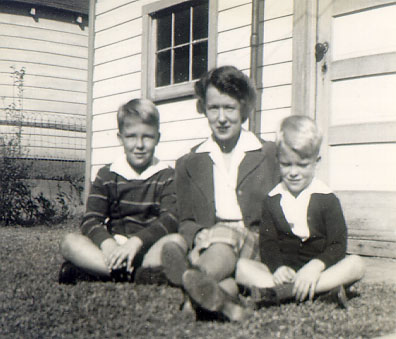

I was a tender six years old in 1943, and America was still tightening its belt in the toughness of World War II. In our house, we stamped tin cans flat after cutting out both ends, kneaded the white grease of margarine yellow by breaking the little pod of color in its plastic sack. We saved string and tinfoil in balls the size of grapefruits. Standing in grocery lines, my mother bought meat or poultry with carefully counted red and blue ration tokens the size of a dime. "The uneviscerated chicken," she'd say, saving a few pennies over the already gutted and singed version. The carcass would become soup. We were poor but hardly noticed; everyone made soup.

Gasoline and tobacco were rationed. We had no car. Because he hated standing in lines, my father sometimes rolled his own cigarettes (occasionally dragooning my older brother and me to load and crank out butts on the big, red Bugler roller). The air-raid warden on our block, daddy had a flashlight, armband and helmet to prove it as he checked the neighborhood during blackouts for tell-tale light. We had dark purple blackout shades on the windows for air-raid drills.

My fastidious mother made laundry soap, sweating over her steaming cauldron of lye and rendered fat on the basement stove, her hair stringy and her arms glistening as she stirred. My school-teacher aunt worked a shift in the small arms plant, which made me think she turned out little doll-like arms, for what I couldn't possibly imagine.

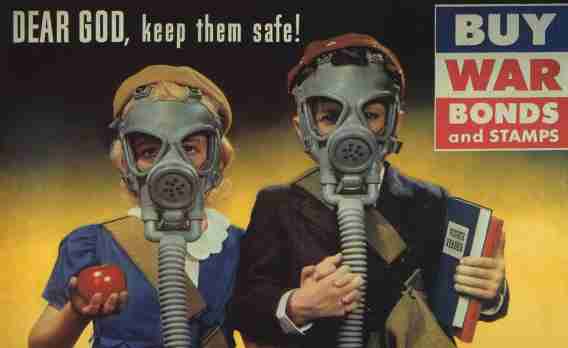

Americans

saved everything they could for the effort overseas. My brother and I

wore

Paper Trooper insignia proudly sewn on our jacket sleeves as we rolled

squeaky wooden wagons bulging with waste paper collected from house to

house to stack next to the schoolyard scrap pile to help the war effort.

Americans

saved everything they could for the effort overseas. My brother and I

wore

Paper Trooper insignia proudly sewn on our jacket sleeves as we rolled

squeaky wooden wagons bulging with waste paper collected from house to

house to stack next to the schoolyard scrap pile to help the war effort.

Every day, we pledged allegiance to the flag standing in a circle around this junk-pile that a grizzled janitor guarded as seriously as any ammo dump: old pots and pans, broken machine parts, clumps of salvaged nails dumped from jars, discarded cookie tins, string-tied stacks of flattened tin cans, dented wash boilers, old plumbing parts. Rising higher each week, the scrap pile stood as tangible evidence of the revenge for Pearl Harbor we would hurl back at Japan once this trash was tooled magically into sleek, merciless artillery shells or bombs.

With a dime nestling brightly in my

pocket to buy a weekly "Victory" savings stamp, I watched with my

friends

for the special glints of metal that signaled treasure: war souvenirs

trickling

back from the fighting overseas. "Lookit! Looka dat!" rat-faced Mertz

would

mutter, nudging me roughly as new prizes appeared--bayonets, German

helmets,

Nazi badges and medals, a black-handled dagger, ammo tins and belt

buckles,

even a real German Luger pistol, with its action sprung open, on which

we longed to get our trigger fingers. In fact, I lost my trigger

finger,

and the one next to it, fighting for freedom that year. I was the first

serious casualty in our neighborhood wars.

We played at war endlessly. We skirmished house-to-house in the alley gangways of our neighborhood, escaping stalkers by leaping from garage roof to garage roof. We hid in the ashpits between the garages on the alley and popped up shooting or swung on doubled clothes-line like conscripted Tarzans from girders at the unfinished addition to the funeral parlor. We communicated with tin-can walkie-talkies and used crude periscopes to see around corners. We made foxholes under mule-high mounds of grass clippings in the park, clutching springy, green sticks called "mud slingers" to leap out in ambush and launch stinging gobs of clay squeezed onto the ends at our not-very-unsuspecting foes.

If we could not craft the latest weapons from wood with coping saw, glue and paint, we had to overwhelm the foe with pre-war, silvery, red-handled Gene Autry six-guns or double-hammered pirate pistols instead of the Thompson subs or blue-black 45s we coveted. But subdue him we did, usually in hilly O'Fallon park across from our house in north St. Louis, where below a sprawling, castellated stable and barn, a deep, shadowy woods was bisected by a running stream flowing towards the Mississippi a couple of miles away.

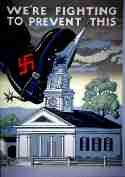

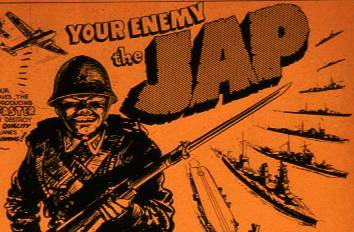

According to our whim, we transformed the stable (built, in fact, in an old, Germanic style) into a Nazi fortress, the woods into forests in France or Germany, or maybe into Guam's dripping jungles. We pointed out Nazi tanks careening along the smooth hills or hunkered anxiously under sycamore "palms" to avoid the chattering machine guns of swooping Jap Zeroes.

We had no GI Joes, no mega-monsters, Power Rangers (except Flash Gordon), no Tojo or Hitler dolls. Our boogie man nightmares had not yet been realized in chainsaw psychopaths or Freddy the Slasher. Our costumes signified, rather than depicted, menace and danger: military patches and ribbons, old Sam Brown belts and kakhi bandoleers, even World War I castoffs--the first real Army Surplus--lace-up puttees and scratchy campaign blouses, a moldering gas mask, my uncle's weighty flare gun, a German helmet into which your head entirely disappeared.

We were mad for war, miming the soldierly exploits we watched with

eye-popping

excitement on the Saturday screen at the 10-cent neighborhood movie

theater,

the O'Fallon. Faithful to our screen idols--John Wayne, Errol Flynn,

Dana

Andrews, Robert Montgomery, Richard Conte--envying their patriotic

right

to do violence, we sniped at Nazis and choked unwary Japs with

imaginary

piano wire.

We were mad for war, miming the soldierly exploits we watched with

eye-popping

excitement on the Saturday screen at the 10-cent neighborhood movie

theater,

the O'Fallon. Faithful to our screen idols--John Wayne, Errol Flynn,

Dana

Andrews, Robert Montgomery, Richard Conte--envying their patriotic

right

to do violence, we sniped at Nazis and choked unwary Japs with

imaginary

piano wire.

Hitler, Tojo, Mussolini--the butt of cartoons to inspire hate and disdain--might fall ten times a day before the withering, mouth-tiring rapid fire of my broomstick-and-tin-can Thompson submachine gun. Or they marched in ignominy, roped around the neck with clothesline, to the alley where we hung our enemies. "Hey, no fair, " dreamy, pudgy Lagerhausen would moan. "I was Tojo yesterday."

While we believed in enemies, the closest we came to real cloak-and-dagger danger was to steal--at Rexall's, Western Auto or Woolworth's. To sharpen our clandestine skills, we'd also try to sneak upstairs undetected to the O'Fallon theater's cry-room. This was a sound-proof, picture-window booth with a row of seats and sound piped in, tucked up next to the women's bathroom. There, war-wives with crying babies (and absent husbands) could still watch and hear the movie. To elude the cold-eyed, wrathful manager won us hashmarks for bravery; to surprise an older kid and his girl and escape the anger of their interrupted smooching was grounds for extreme valor.

In O'Fallon park one warm autumn day in 1943, valor was in short supply: the war went badly for the Allies. In a wide, clay gully eroded over years by a broken storm sewer pipe, I and some sidekicks were pinned down under the mouthing of a murderous cross-fire from neighborhood Nazis surrounding us above. From our movie experience, we knew we had to "break out" but the only escape was up the steep-sided gully banks into the enemy's fire. "Move out!" we all shouted frantically to each other. We careened around like cockroaches dumped from a can.

My brother, who was nine, had brought his Boy Scout hatchet to battle and chopped with a mad, furious, Teuton cackle at the gully rim to shower us with clods of dirt. As we tried to scramble up the gully wall, his cascades--the mortar fire of make-believe--rained down to drive us back. Like wet cats trying to scale a slippery bank, we struggled up and I, somehow, made the rim, scrabbling desperately for a hand-hold as he swung his hatchet to loose a last deadly barrage. The hatchet bit my reaching hand, the lefty I favored, slashing off the first two fingers near the middle joints and almost a third.

I fell back into the pit. But I remember to this day a scream, a cry as desperate, anguished and horror-stricken as any animal's struck down in fatal surprise. Not my scream; his. And the hatchet...He sent it sailing wildly away from him like some suddenly ferocious, wild thing that had turned and bitten him, not me. Then, he ran. What happened to the others, I don't remember. My world went black.

I woke up, likely only moments later, to a weird, buzzing silence, at the bottom of the gully, utterly alone and spouting blood. Gagging and snuffling up out of the hole, I struggled towards home, squeezing my wrist, sick with the sight of my own blood, snotty with fearful tears. I paraded my severed stumps before me, the red-running hand a banner to shocked disbelief. It was a thing apart, alien, foreign--like the thorned, flaming, bloody sacred heart of Jesus I puzzled over as a Protestant sneaking into Our Lady of Perpetual Help to eavesdrop on mass. A fine, piercing wail, my mother remembered, announced my impending arrival from several blocks away. My Purple Heart would be awarded with a little tarnish.

My father was at work. My mother watched me stumble up the front steps.

She was so stunned, I pushed on past her, ravaged for some reason by a

gnawing thirst, and headed for the kitchen sink. Nothing mattered more

than that thirst; I put my mouth on the spigot and drank and drank,

until

suddenly my mother was there, gently, firmly easing me away.

She ran cold water on my hand. Her face dented white with grief, concern and anger, she saw a third finger half cut through, hanging, and moaned. Then she wrapped the hand in a towel, as if to hide it. "Where's your brother?" she demanded darkly. I shook my head. "That damned hatchet," she said, almost in tears.

She raced next door to borrow a neighbor's car, came running back in her quick, bird-like steps to help bundle me into the older woman's black Buick and we peeled off to the nearest hospital. I remember the hard-pressed lips of both women, how they sighed and shook their heads in tandem as the hearse-like Buick, rocking like a boat, pitched through intersections and bumped over cobbled streets. Our neighbor's usually carefully combed white hair stood out as if electrified. "What a damn-fool thing," she muttered over and over, as if to fill my mother's stony silence. "This damn-fool war...Little boys! I declare!" She kept trying to smooth her hair as she drove.

My mother's anger burnt itself out in the car but her jaw was hard as she hustled me into the emergency room. I was frightened, drained by the pell-mell, screeching journey. White uniforms surrounded me. They stuck me with something, quickly, wordlessly, in my arm. The break-out kid who triumphed to the gully crest became a whimper in a white hospital shift, prostrate on a gurney. My injured hand was crooked by my head as though caught and frozen in mid-salute, but covered now in something soft and bandage-white.

Leaving my mother behind, a nurse in a peaked hat wheeled me past the harsh, slapping metal sound of crashing gates into an elevator with a too-bright light overhead that made my eyes blur. Men and women in white gowns, some with masks, surrounded me. On my back, I felt exposed, sorrily exposed as I looked up at them looking down at me, and the rising elevator made my stomach feel hollow. One robed man reached out to lift the white covering over my hand, peered for a moment and shook his head slowly. Others looked on, nodding in refrain. I had seen that before in movies! The lifted sheet, the shaking head, the slight, sad sigh escaping the doctor's lips. And so, at six, I wondered: am I going to die?

And

then a sudden shell-burst of activity: the slapping gates opened, the

rolling

bed sped off, I smelled the strong medicine smell and struggled little

when they shined a strong light in my eyes, stuck me again and, with

soothing,

reassuring words I did not understand, put a mask over my face. Another

face, uncomfortably close, told me to breath, to breath. First, the

ceiling

disappeared; then the light; then white, moving parts of bodies

dissolved

in dark. I wanted to see my father.

And

then a sudden shell-burst of activity: the slapping gates opened, the

rolling

bed sped off, I smelled the strong medicine smell and struggled little

when they shined a strong light in my eyes, stuck me again and, with

soothing,

reassuring words I did not understand, put a mask over my face. Another

face, uncomfortably close, told me to breath, to breath. First, the

ceiling

disappeared; then the light; then white, moving parts of bodies

dissolved

in dark. I wanted to see my father.

When I woke up, twitching like a puppy having nightmares, my mother sat, reading, next to my bed. She looked so tired. The shadowy room was divided with a gauzy partition; behind it, the rasping sound of labored breathing. My mother smiled and ran her fingers gently through my hair. My hand was a huge, white lump, heavy, tingling, elsewhere. Above my head, a fan droned lazily. A sweating pitcher of ice-water stood on my bedside table, with a bent glass straw in a tumbler. I asked for water and my mother carefully poured the tumbler full and moved the straw to my lips.

My father came later, to stand with his black brows drawn together, to touch my shoulder gently and ask, "How's my brave little man?" before he gathered me in his arms.

The next day, I was moved to a children's ward, where the moans and cries in the night made me think of wounded soldiers in a big tent under dripping palm leaves. The kid next to me, groggy, silent, wore a lopsided bandage like a huge, white turban that dragged his head to one side. Across an aisle, a boy with red hair and both arms in plaster casts exchanged sheepish, sleepy looks with me that made me feel like we were doing penance. My bed was close to a red-glowing night light. I lay listening to the softs and sharps of night sounds echoing in the glimmering halls, quiet as a tick, my left hand throbbing a kind of reassurance, my right hand over my heart.

The

next morning, my parents arrived with a gift-wrapped box they said was

from my brother. It was a store-bought walkie-talkie with cardboard

housing

covered in camouflage paper, wooden aerials and mouthpieces. And its

black,

shining string carried sound much better than the tin-can

walkie-talkies

we crafted clumsily at home with plain white wrapping string. By that

afternoon,

a boy across the ward and I were crackling orders to help beleaguered

marines

pinned down on distant beaches, while nurses ducked under the string.

My

brother did not appear; no word was spoken of his whereabouts. Only

decades

later did I stop to reflect that this present spoke of communication,

of

redrawing lines between two people, re-establishing contact. My father

had depths I never recognized.

The

next morning, my parents arrived with a gift-wrapped box they said was

from my brother. It was a store-bought walkie-talkie with cardboard

housing

covered in camouflage paper, wooden aerials and mouthpieces. And its

black,

shining string carried sound much better than the tin-can

walkie-talkies

we crafted clumsily at home with plain white wrapping string. By that

afternoon,

a boy across the ward and I were crackling orders to help beleaguered

marines

pinned down on distant beaches, while nurses ducked under the string.

My

brother did not appear; no word was spoken of his whereabouts. Only

decades

later did I stop to reflect that this present spoke of communication,

of

redrawing lines between two people, re-establishing contact. My father

had depths I never recognized.

A few days later, the doctor said I could go home. My father carried me up the front steps traversing our steep lawn, stepping carefully because he had a permanently bent leg from a childhood riding accident. There stood my brother, flashing a precarious smile of welcome and a hesitant wave. My hand, spread on a splint and wrapped in plaster bandage halfway up my skinny arm, lay snug in a sling; my other arm around my father's neck, I could not wave. A get-well card--two soldiers talking on walkie-talkies--my brother had drawn and colored with his already careful, accomplished hand, hung from a thread above the door. "From one brother to another," it said. "Welcome home, Stevie," he said.

My brother and I never talked about this wound, not for 40 years. Nor did my parents. It was as if something mysterious, or unmentionable, had happened. The episode seemed to disappear under autumn's falling leaves. But I felt cheated. How could he at least not tell me he was sorry? Why wouldn't my parents speak? This wound was real.

That damn hatchet disappeared. And yet, I sympathized. I understood how his hatchet, over which I had burned in envy, was as necessary to him as Prince Valiant's sword or Captain Midnight's secret decoder ring--a signifying advantage, an icon of leadership among a cohort of toy swords and home-made bazookas. The thing was real.

Chunky, bullying, more driven than

me even then, my brother had always edged closer to the danger of real

damage, of action signifying authentic boldness--and recklessness. He

believed

too much in battle and used his weapon rashly, he was so deep in war. I

kept silent, as if he too had sustained a wound.

Unsuspected gifts rained down, however. Days out of school were like a string of Saturdays, when my mother allowed me to listen to radio serials ("Terry and the Pirates", "Sky King", "Sergeant Preston of the Mounted Police", "Captain Midnight") and play in my bed or see a movie matinee. I saw two movies in a week, with ice cream after at Velvet Freeze. My first day back at school, I realized I didn't want to lose the cast too soon. It inspired awe, conferred celebrity. When asked, I displayed it magnanimously like a trophy, a pass to a world of real injury my friends feared. "How bad did it hurt?" they asked me, followed closely by, "What does it look like now?" Like Tom Sawyer with his toe, I had my talisman. A veteran at seven, I basked in power.

I caught on fast. I got offers to tie my shoes, unbutton my bookbag,

unwrap

my lunch. Geraldine and LaRee cranked the pencil sharpener for me; for

weeks, I bristled, single-handed, with rapier-pointed pencils (even

though

I couldn't write a word). At my desk, the only hand I raised to answer

questions or request the toilet was my white, plaster beacon. If

uncalled,

I might let it bang down on the desk, thinly disguising pique as

clumsiness.

LaRee, whose hillbilly twang inspired oddly possessive notions in me,

left

a hand-lettered card on my desk. "You ARE Brave," it said.

I caught on fast. I got offers to tie my shoes, unbutton my bookbag,

unwrap

my lunch. Geraldine and LaRee cranked the pencil sharpener for me; for

weeks, I bristled, single-handed, with rapier-pointed pencils (even

though

I couldn't write a word). At my desk, the only hand I raised to answer

questions or request the toilet was my white, plaster beacon. If

uncalled,

I might let it bang down on the desk, thinly disguising pique as

clumsiness.

LaRee, whose hillbilly twang inspired oddly possessive notions in me,

left

a hand-lettered card on my desk. "You ARE Brave," it said.

The zenith of my war-time trajectory came one day among kids playing marbles in the apron of dirt surrounding the schoolyard sycamores. Out of commission, I stood and watched. "Here, I'll shoot for you," said the marbles ace, an older boy who never ever noticed me. When he slammed his shooter into a hapless rival's and knocked it out, I picked it up and spotted it back in the circle, nodding to the loser, thanking the ace.

And yet I learned, first-hand so to speak, and early, that no wounds

are

glorious. The plaster came off in weeks. The gauze bandages dwindled

each

time they were refreshed. The splint was discarded and the bandage

outlined

my stumps. Finally, I was left with two pale stubs laced with ugly

black

stitches and a crooked third digit the doctors saved but couldn't

straighten

out. After those stitches had been painfully yanked, after my angry

tears

had dried, I hid my pale, shrunken hand and longed again for my

hard-thumping

gauntlet, my moment of celebrity as a casualty of war.

And yet I learned, first-hand so to speak, and early, that no wounds

are

glorious. The plaster came off in weeks. The gauze bandages dwindled

each

time they were refreshed. The splint was discarded and the bandage

outlined

my stumps. Finally, I was left with two pale stubs laced with ugly

black

stitches and a crooked third digit the doctors saved but couldn't

straighten

out. After those stitches had been painfully yanked, after my angry

tears

had dried, I hid my pale, shrunken hand and longed again for my

hard-thumping

gauntlet, my moment of celebrity as a casualty of war.

TIME SNAKES: Recollection

By S. K. Oberbeck

I lost the first two fingers on my

left hand during World War II when I was six. We got separated playing

a war game in which I was a Nazi prisoner trying to escape from a deep

gully eroded in a park near our house in St. Louis. I was not alone. Our

captor rained dirt down on us with a hatchet as we tried to climb to freedom.

I got to the top, just as the blade of the hatchet bit into the edge of

the gully I had just reached for. I wore my big, white, plaster cast like

a proud battle ribbon for a few months and a few years later, the war came

to a close.

To be a kid in those days was to be immersed in war games: guns, trench knives, hand-grenades--an arsenal of wound-making, gut-ripping death. We died a thousand times, riddled with each others’ deadly, mouth-tiring machine-gun fire. And we killed each other copiously, falling to rise again, falling and rising, endlessly resurrected. We spent years recreating movie battle scenes popping in and out of foxholes we dug in spacious, rolling O'Fallon Park.

But the older we got (I was eight when the war ended), the more we tired of being blown up. By 1945, we began to rechannel our military might in the direction of other, less odious enemies than Tojo, Mussolini and Hitler: our focus changed to girls.

They affected us more than we knew. In summer, we gathered and cured what we called "lady cigars," which we smoked to impress the girls and each other. These slender, almost foot-long pods hung from O'Fallon Park's many catalpa trees. We had to climb for them in the dense, deep-green canopy of almost heart-shaped leaves. Then, on one garage roof or another, we ranged the raw pods to dry on newspapers spread on the flat, sizzling tarpaper until the sun turned them from circus-lizard green to chocolate brown.

To master this husbandry, you had to watch the drying pods as carefully

as hatching chicks or tadpoles: too much sun cracked the outer shell; the

smoke wouldn't draw; you'd have a dud. Inside their hard, brown skins,

feathery seeds encased a wrinkled, licorice-colored core resembling a starved

vanilla bean. This resinous core gave the lady cigars their kick. The seed

filler kept the husk burning like punk, igniting the core's tarry, noisome

flavor. Their acrid smoke was foul, oily, stinging. They were awful and

we loved them, as we strutted down the alleys wreathed in yellowish, fuming

clouds or slouched like hoboes as we smoked behind bushes in the park.

We did not inhale; inhaling threatened wracking, choking cough and nausea. The face turned sickly green; the stomach churned and crash-dived. We practiced blowing smoke rings and keeping our tongues from being burnt. The bravest of us smoked conspicuously at the edge of the park playgrounds, alert to counselors who'd scold us but more alert to girls who'd notice our bravado.

Smoking was a big deal then, especially in the movies. "Smoke 'em if you

got 'em!" was a cinematic dogface refrain when danger threatened, a line

usually intoned before servicemen mounted a landing or scrambled their

flying machines to save our bacon in a furious hail of flak. Like the native-American

calumet, shared smoke in foxhole or squad room broke tension, celebrated

survival, made men brothers. Maybe we smoked because Richard Conte dipped

his helmet a certain way to hide the flame from his Zippo. Maybe we smoked

because Ricky and Rhett smoked. Or because of how the smoke curled up Bacall's

nose before she blew out.

Smoking was a big deal then, especially in the movies. "Smoke 'em if you

got 'em!" was a cinematic dogface refrain when danger threatened, a line

usually intoned before servicemen mounted a landing or scrambled their

flying machines to save our bacon in a furious hail of flak. Like the native-American

calumet, shared smoke in foxhole or squad room broke tension, celebrated

survival, made men brothers. Maybe we smoked because Richard Conte dipped

his helmet a certain way to hide the flame from his Zippo. Maybe we smoked

because Ricky and Rhett smoked. Or because of how the smoke curled up Bacall's

nose before she blew out.

We harvested and cured many more lady cigars than we could possibly consume, as if hoarding increased our stature. This hunger to possess was one symptom of our youthful collecting mania--comic books, bottle caps, baseball cards, packs of streetcar-fare transfers, foreign coins, stamps. It almost didn't matter what; accumulating was the object of the game.

Perhaps wartime rationing honed an edge on our desire. We felt a mild itch you couldn't scratch. To buy meat, my mother had to dole out our allotment of red and blue meat tokens, dime-sized wafers punched from a hard, pressed fiberboard or use little booklets of gray-blue ration stamps for other essentials. Butter disappeared: we vied to crack the color capsule in the plastic bag of white grease that kneading turned to yellow margarine. Tobacco was rationed; so was gasoline: since factories were dedicated to turning out war materials, no cars were being made either. Tires went overseas anyway. Grown men rode bicycles.

Since cigarettes were rationed, they were even more prized than usual.

My father often rolled his own rather than stand in a ration line, or dragooned

my bother and me to roll cigarettes in the basement on a big, red Bugler

roller. My Aunt Mabel chain-smoked Marvel, Ace, Wings--the lower-quality

wartime brands sitting in for the Camel, Chesterfield or Lucky Strike shipped

to troops.

Since cigarettes were rationed, they were even more prized than usual.

My father often rolled his own rather than stand in a ration line, or dragooned

my bother and me to roll cigarettes in the basement on a big, red Bugler

roller. My Aunt Mabel chain-smoked Marvel, Ace, Wings--the lower-quality

wartime brands sitting in for the Camel, Chesterfield or Lucky Strike shipped

to troops.

In many of our rituals, the unconscious nucleus was female. We hunted garter snakes in early summer, just after the park playgrounds opened. Each year, we mounted a snake hunt in what we dubbed "Snake Hollows"--a parcel of vacant, overgrown, insect-buzzing lots where long ago brick tenements had been demolished. This ritual involved an odd digression, one we never questioned but never truly understood.

To reach Snake Hollows, we passed by a Catholic church people called "Pink Sisters," built massively in brick, on a foundation of granite, with a high, granite wall, forbidding in its bulk, that surrounded and sheltered a three-story cloister next to the cathedral. Behind this stony separation--a world away, it seemed to us--lived an order of nuns, called variously "Pink Sisters," "Little Sisters of Poor," "Daughters of Christ" (mostly by non-Catholics I realized later), women committed to poverty and silence.

These women behind the wall fired our imaginations. We knew they had signed

up for a hard life of constant worship and self-sufficiency, that they

never left the convent grounds. Occasionally, we scaled their slightly

inward-sloping barrier to see what lay hidden on the other side. It felt

like climbing a prison wall, escaping. We half expected to find nuns cobbling

shoes or washing clothes in a steaming kettle. But we rarely saw a nun

outdoors. And if we spotted one from where we hung like Kilroys peering

over the crest of the wall, she turned her face away and hurried inside.

These women behind the wall fired our imaginations. We knew they had signed

up for a hard life of constant worship and self-sufficiency, that they

never left the convent grounds. Occasionally, we scaled their slightly

inward-sloping barrier to see what lay hidden on the other side. It felt

like climbing a prison wall, escaping. We half expected to find nuns cobbling

shoes or washing clothes in a steaming kettle. But we rarely saw a nun

outdoors. And if we spotted one from where we hung like Kilroys peering

over the crest of the wall, she turned her face away and hurried inside.

The notion of women without men intrigued us. Celibacy was not a concept we understood; but we knew these women had nothing to do with men. The war years gave us glimpses of women suddenly alone. Where fathers, sons, brothers had gone to fight stood a palpable vacuum, a space the women moved around, sighing. We saw sisters and daughters hanging clothes, carrying grocery bags or tending toddlers--standing in for working mothers. We saw the kindness women shared, the forbearance. And we saw their tears, grinding loneliness and sometimes boozy betrayals we scarcely understood. We saw rivalry too; anger, resentment; two women in a screaming, hair-tearing fight through the window of the corner tavern one night.

Girls certainly puzzled me. I never had a sister. Even the girls in Our Lady of Perpetual Help's school yard, dressed in spiffy blue and white uniforms, seemed to us inscrutable specimens of a giggling, chattering, evolving other species. Grown women we could relate to as mothers. But nuns were like creatures from outer space. Yet still they hid at the center of another ritual: we watched them. Braving discovery and reprimand, we frequently sneaked into the small cathedral to spy on the nuns at prayer. They took turns doing vigil in the wavering, candle-lit shadows behind ornate iron grills flanking the altar. To watch them, these holy women, plucked at our confusions. Certainly, it added a dimension of mystery and somehow deepened for me the enigma of woman.

To Protestant, mostly Lutheran German kids, accustomed to a robust, no-nonsense

Gothic simplicity, the rococo, color-splashed, Catholic interior heightened

this aura of mystery. The air fumed with incense. Spears of sunlit red,

green and purple lanced down from high, peaked windows. Saints stared accusingly

from darkened niches overhead. The Blessed Virgin beckoned. The stations

of the cross shone like holy billboards advertising suffering and redemption.

Thorny, bleeding hearts abounded.

To Protestant, mostly Lutheran German kids, accustomed to a robust, no-nonsense

Gothic simplicity, the rococo, color-splashed, Catholic interior heightened

this aura of mystery. The air fumed with incense. Spears of sunlit red,

green and purple lanced down from high, peaked windows. Saints stared accusingly

from darkened niches overhead. The Blessed Virgin beckoned. The stations

of the cross shone like holy billboards advertising suffering and redemption.

Thorny, bleeding hearts abounded.

Sometimes the stony silence was torn by a plaintive chant, like softly shattering crystal, as the nuns sang in Latin. Dark and shadow were different here too: deeper, even threatening. Catholic shadows held more menace than our stark Lutheran shadows; they pulsated in the cool, shimmering gloom like moisture-laden storm clouds.

We never considered the formal worship that was in our future; this was laced with an excitement, an illicit thrill I never felt later. We strained to see through, to penetrate the garnet glimmer that banks of votive candles threw from the back of the church, where we knelt with heads half-bowed--our Catholic camouflage--to avoid discovery.

And they kept silent vigil on their knees, as unmoving as adoring statues in a crèche. These nuns, like beings disembodied, were at first simply objects of our morbid curiosity. Motionless, they seemed so otherworldly, kneeling with folded hands behind ornate iron filigree, gowned in gray-blue uniforms and pink veils under white, starched collars and hats. We waited in an answering silence, poised to detect a flicker of life--a movement of folded hands, a bowed head nodding in the sheen of altar candles. We listened for a sneeze, a cough. Sometimes, it became a breath-holding war of nerves. Like staying still to sight a rifle, to focus purely on the target. Our knees burned. How could they kneel so long without moving? Could they be wax? Were they really real?

Another question plagued us: were they really shaved bald under their ornate hats? Once, walking in a band of my buddies, I looked up to see an unhatted, unveiled nun looking down at us from the topmost window in the hulking convent’s facade. My upturned face must have flashed like a deer’s white, warning tail: instantly, she drew back and disappeared. But I saw hair, blackbird-dark, before her image faded to empty glass. And I realized with a sudden thrill that she must have been watching us.

I sensed an audacious, dangerous beauty in this awesome immobility, this life-long dedication: "brides of Christ for all eternity," I remember some adult--this one no doubt Catholic--saying. Shut up their whole life, I thought. It seemed a suicide mission, giving up such freedom, like throwing life away. We shuddered just to think of it.

At seven or eight, we were fierce for freedom, for the life teeming outside those convent walls, especially in the sweltering days and steamy, kick-the-can nights of St. Louis in summer.

Those nights held special neighborhood promises: the ting-a-ling bell of the hot tamale man's cart with its squeaky baby-carriage wheels; the Popsicle man in a policeman's hat, with his bike-driven ice box fuming with dry-ice you dared not touch; the satisfying clunk of floating ice blocks and shining melons banging the sides of Sam the Watermelon Man's big zinc tank under a fluttering canopy; the changing concentric rings of pastel water lofting and dipping in revolving, colored lights at Pevely Fountains, a drive-up dairy and ice-cream bar that families walked to in the evening because gasoline was rationed.

Days, we exercised our itch to run, to roam. Though boisterous once we clambered down the steps towards the snake hunt and left Pink Sisters behind, we went silent again as we sneaked into the Hollows, crouching like point men in a jungle. The garter snakes, we knew, could feel our footsteps.

We entered their territory on tip-toe.

A rubble of stones, broken bricks and chunks of foundation granite were

overgrown with trash trees, vagrant canes and strangler vines in the uneven,

humped terrain, like a battlefield the earth had only partly digested.

It was a perfect breeding ground for snakes.

We entered their territory on tip-toe.

A rubble of stones, broken bricks and chunks of foundation granite were

overgrown with trash trees, vagrant canes and strangler vines in the uneven,

humped terrain, like a battlefield the earth had only partly digested.

It was a perfect breeding ground for snakes.

In this sanctuary, they tended to hatch under stone slabs and huddle in bunches. As we pried up stones, sun would startle the still-sluggish, knotted, little reptiles, slippery yet dry, fast as quicksilver in the sudden light. There was an instant of repose--as if time itself had hesitated--before they detonated into action. Their viper eyes belied their smooth, gracefully spiraling harmlessness as they darted in the grass to escape our eager fingers. Their spines striped white against a soft gray and dull green, they coiled in sinuous postures of the feminine, curves and loops both shy and inviting. Scales no bigger than pencil-points, they thrashed frantically but rarely bit.

We gathered them, slithering and whipping, into our shirts and walked, waiting for them to calm. A tee shirt wouldn't work, only a loose, tuck-in shirt with enough extra cloth to create a pocket, folds to hide the movement. Only a few boys carried the concealed weapons of this sweet ambush and, often, I was one. And when we were armed, we turned back towards the park's wide, greening hills and made for the playgrounds, for quarry: the girls.

Our mission? To lure some unsuspecting

girls to the big swings. These hung on 15-foot chains, with slab seats

wide enough for one to sit and one to straddle standing up. You invited

a girl to sit and then you took her up. To "take her up" meant pairing,

a kind of courtship, in which the boy powered the swing while the girl

sat and enjoyed the ride.

The boy stood on the seat, a foot on either side of the sitting girl, who faced him. Reaching up to clasp the chains, he arched and pushed, bending to heave the combined bodies forward, slowly at first, then faster, pausing to ride the trajectory to the lip of the backswing, then surging forward again, his body flexed towards her dodging face, to rise and strain in the push and lag of each progressive pendulum arc, to lift his partner up higher and ever higher, the boy spread-eagled in the rushing air, the girl's hair sailing, head thrown back, knuckles white on chains.

It shook the senses: a blur of sliding perspective, a giddy swoop of shifting scene, a clenched feeling of being so close to something, so attached to the center of something, a veil of whistling pressures through which we rose and fell, trailing cries of jubilation. So strong our bent for deception, I doubt we ever considered what hovered mere inches from our partner's nose as we swooned through the hot, buzzing summer air, sweat streaming, towards some zenith.

And snakes still slithering in our

shirt.

Unawakened, our fresh desire was aimed exclusively at mischief: to rise so high, to create such momentum, we took a captive and the captive could never jump off. As we humped and strained, the snakes might thrash or find their way out. And then the game would be lost. But if we reached our summit, and then, loosing one hand (supreme moment of daring) fumbled out a snake, or better yet a handful, to dangle in the screaming, now-horrified face struggling vainly for escape--that was true rite, the stuff of primitives.

For how could these girls not know, not see through our ambush, not spy snakes squirming in our shirts? Not notice our ill-disguised, wicked grins? Not cut us off at the knees before we even started the subterfuge? Of course, some did. Some were uninitiated, virgins in the side-winding strategy by which we made our first ovations to girls. But most cooperated. They screamed and giggled and played along--no different from aboriginal children, or pigmy kids we saw in scratchy Erpi classroom films, who went giggling through similar rites.

And why this hidden streak of feeling almost like revenge?

Things we sensed but did not yet know: a power girls already had over us, in our thoughts, our chip-on-the-shoulder denials, in the little dangers we rehearsed at the stage of their gaze in hopes of attracting their scant attention, the things they said behind their hands to each other, even a vague dread of their import in our futures.

For whether we stood on swings or knelt on stones, a strange continuum unfolded here: incense and candle-flame; unknown shadows suggesting unknown spaces; moist seductions of heart and hidden body; the iron focus of those kneeling forms, the whistling air and breath-taking motion...These intimations swirled for us like smoke or shadows through which we could not see.

And

finally, as we outgrew our weaponry, exchanged trench-knives and rifles

for hockey sticks and baseball bats, we began to see these whispering,

squealing creatures in a different light. That summer, one of our gang

began to comb his hair before we hit the playgrounds and we all aped his

combing vanity in louche exaggeration, making wet kissing sounds on our

bare arms. But under the lid of our self-conscious hilarity, the first

siren strains of a coming urgency sounded and--as the cobra rises from

the basket--sex lifted sleepy eyes and spread its hood.

And

finally, as we outgrew our weaponry, exchanged trench-knives and rifles

for hockey sticks and baseball bats, we began to see these whispering,

squealing creatures in a different light. That summer, one of our gang

began to comb his hair before we hit the playgrounds and we all aped his

combing vanity in louche exaggeration, making wet kissing sounds on our

bare arms. But under the lid of our self-conscious hilarity, the first

siren strains of a coming urgency sounded and--as the cobra rises from

the basket--sex lifted sleepy eyes and spread its hood.

While we talked and joked about it, real sex for us at eight or nine was unknown territory, except for movies and tales--or boasts--of older brothers or school yard clinicians, passed down through many editions, as in the game of "telephone".

At school, precociously endowed Wanda-Lee could sometimes be spied mixing it up with a boy in the cloakroom, once with his hand way up her dress. When I was maybe ten, another coming attraction, a cute, blonde girl named LaRee, sat on my stomach one steamy summer Saturday morning and dripped melting grape Kool Aid ice cubes onto my bare chest, squirming and laughing as her tickling, insistent fingers spread around the sugary stickiness.

We had elaborate class room schemes, involving little pocket mirrors we stole from Woolworth's or Rexall's, for catching a look up girls' dresses. We dropped a pencil as one walked by, or pushed a book off the desk, then feverishly reached down a mirror-clutching hand, trying to aim its tiny focus up her skirt to reflect her pants (or, our fervent hope, lack of pants). This actually worked about as well as trying to hit a frantic bird in a barn with a slingshot. Lottery odds. But how we tried.

Movie sex was tame in those days. At carnal moments, the camera panned to blowing curtain or guttering candle flame. In fact, things were usually hotter in neckers' paradise, the last two rows of seats at the O'Fallon theater, than up on the screen.

Another feat of deering-do was to entice uninitiated girls at the movie up to what was called "the cry room". This picture-window, soundproof room upstairs by the ladies restroom contained five theater seats and a speaker to play the movie soundtrack. Here, mothers with bawling babies could watch the movie without disturbing the whole theater.

Women without men regularly went to

the movies alone and brought their babies along, especially on "Dish Night"

when they could win free kitchen crockery as door prizes. The cry room

was not always in use, however, and to sneak a girl past the gimlet-eyed

manager by the popcorn machine for a little back-row action upstairs was

a feat of steely risk and raw courage. What bumbling, romantic moves we

could inflict on the hapless girl were less important than running a gantlet

of possible menaces: mothers, older guys with the same idea, the manager

and the lone, one-eyed usher who we all joked had already been embalmed

at nearby Math-Hermann funeral parlor.

Pornography in the 1940s was hardly even a word. Girlie magazines beckoned

in barbershops. A burlesque show downtown--and its adjacent peep-show parlor--we

discovered much later in life. At Royce's Pipe Shop, an older kid packed

a deck of cards with 52 naked ladies flashing bare breasts but coyly covering

the other good stuff, which he let us glimpse behind the counter. The two

"jokers" were women with men's genitals superimposed, a shocker to curious

kids!

Pornography in the 1940s was hardly even a word. Girlie magazines beckoned

in barbershops. A burlesque show downtown--and its adjacent peep-show parlor--we

discovered much later in life. At Royce's Pipe Shop, an older kid packed

a deck of cards with 52 naked ladies flashing bare breasts but coyly covering

the other good stuff, which he let us glimpse behind the counter. The two

"jokers" were women with men's genitals superimposed, a shocker to curious

kids!

We made crude drawings of people "doing it". Once, on our rambles in the park, we came upon a man and woman doing it with great gusto behind bushes, and stood transfixed. And then we discovered, quite by accident, a treasure trove of clever carnality that marked indelibly our notions of what lay ahead: the eight-page bibles.

We found them ash-pit hunting. There must have been 20, wrapped like a brick in newspaper with fussy, many-knotted neatness in one of the ash-pits. Ash-pits were not pits at all, but brick or concrete-block enclosures five to six feet high between garages on the alley. There, homeowners threw ashes, clinkers, bottles, cans and any other trash that wasn't garbage, to be emptied by trucks from the alley. We scavenged them regularly for useful trash and weird souvenirs. The eight-page bibles were a major strike.

These midget comic books, cartoon line

drawings in black and white, were only a little larger than a baseball

trading card. They were normally eight pages, on rough, pulp paper, with

single pages sometimes divided into two smaller panels. We had never heard

of them. Only later did we learn they were called "eight-page bibles".

For as we broke open the tight, little bundle and fumbled out the contents,

we found old friends--our Sunday morning buddies--doing the most amazing,

nasty things to each other.

Here were familiar funny-paper characters--drawn with satisfying authenticity--Dick Tracey and Tess, Jiggs and Maggie, Dagwood and Blondie (and the kids!), Nancy and Sluggo, L'il Abner and Daisy Mae, even the Katzenjammer Kids--all wound up, connected, linked in wondrously smutty, carnal combat. We were dumbfounded, delighted, perplexed, skeptical to see such things were done in such a way. We hardly had names for what we were seeing.

Taboos tumbled before our incredulous eyes: not only did Dagwood do it to Blondie, his signature cowlick erect and drops of sweat springing off his head, but Alexander did it to Cookie--and then they switched! Forward, backward, upside down. In the end, a ravening, still unsated Dagwood eyed the cringing dog, Daisy, lasciviously as a bushed but maniacal Blondie urged him on.

Cap in hand, Sluggo took the now-bubble-breasted Nancy doggie style, as

scraggly Jiggs, still top-hatted and champing his cigar, mounted Maggie

like a grinning bulldog and puffed great clouds of smoke and salacious

celebration. And here was Mickey doing what mice normally do to Minnie,

and spinach-gobbling Popeye and bullying Bluto tussling over turns with

unruffled, oddly pneumatic Olive Oyl. All the bodies were similarly drawn,

but with the authentic-looking cartoon heads superimposed.

Cap in hand, Sluggo took the now-bubble-breasted Nancy doggie style, as

scraggly Jiggs, still top-hatted and champing his cigar, mounted Maggie

like a grinning bulldog and puffed great clouds of smoke and salacious

celebration. And here was Mickey doing what mice normally do to Minnie,

and spinach-gobbling Popeye and bullying Bluto tussling over turns with

unruffled, oddly pneumatic Olive Oyl. All the bodies were similarly drawn,

but with the authentic-looking cartoon heads superimposed.

Each little tome we devoured uproariously yet with trembling hands. This smut inspired a kind of reverence, produced a weird body tightness, awakened a higher caliber of fantasy to see such slick and slurpy permutations and combinations we scarcely imagined and would not see again until R. Crumb took up his pen in the hippie '60s to revive this cartoon art form with nonchalant hilarity. Who was this clever pornographer, 30 years previous, scandalizing the Sunday morning funny-paper crowd? We never found out.

Years later, I remembered our crude discoveries when writing an article

on Japan's cartoon pornography--men hauling their own huge phalli on wheelbarrows

or giant members carried by bearers in pomp and splendor, like Sudan-chair

royalty. Simple ink drawings on Manila paper had the texture of that rough,

wartime pulp. And a flash of memory for feelings: the humor, the funny-paper

familiarity, the cartoon format that smoothed a disturbing edge off what

we sat there taking in.

Years later, I remembered our crude discoveries when writing an article

on Japan's cartoon pornography--men hauling their own huge phalli on wheelbarrows

or giant members carried by bearers in pomp and splendor, like Sudan-chair

royalty. Simple ink drawings on Manila paper had the texture of that rough,

wartime pulp. And a flash of memory for feelings: the humor, the funny-paper

familiarity, the cartoon format that smoothed a disturbing edge off what

we sat there taking in.

We hid away an entire, summer Saturday afternoon in a cavernous, dark shed by the alley, processing and savoring those stunted pages by chinks of sunlight, filling our heads with burning questions, vague alarms, secret runes that softly abraded childhood innocence. With vows of secrecy, we reverently rewrapped and hid them, reconvening the next day--Sunday--to sit cross-legged in furious concentration, poring over the little booklets and smoking lady cigars until we were sick. Each time, we retied and rehid our precious bundle behind boards in the barn-like shed on the alley behind Kenny McClain's house.

But the story of our sex-book serendipity must have spread beyond our circle. A few days later, the bundle was gone. We kept our ears open and our senses sharp to discover who could have raided our cache. We conducted a mini-inquisition too, surrounded by burning candles, pledging no reprisals even if one of our select band had betrayed us. Our treasure never resurfaced.

But seeds had been planted. We never read the Sunday funnies again without dissolving into uncontrolled fits of laughter, which puzzled our parents and siblings no end. And even now, when I happen across any of the old characters (now mostly gone except for Nancy and Blondie) in the newspapers, they occasionally threaten to tear off their clothes and have at each other, reveling once more in secret passions and forbidden lusts.